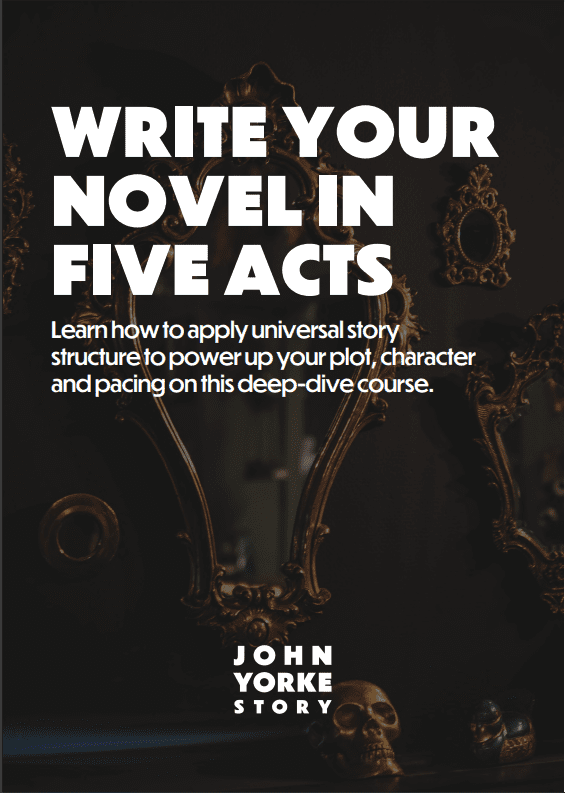

In Into The Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them, I make the case that story structure is hardwired into human perception: all stories are essentially the same because they reflect the way in which we make sense of the world.

Once we understand that stories are not just about entertainment, but a reflection of how the human brain works as it communicates with others, we can see the enormous opportunities this provides for business.

All aspects of business rely on developing engaging content and forming engaging relationships; at the core, it’s about telling stories — about your brand, your product or services, your campaigns, your people, your aims and goals — and your successes.

This makes understanding storytelling an essential tool for business. On the ground, few people have a practical understanding of what stories are, and how to weave them around brands, products and services.

To apply stories to the commercial world, you need to understand how they work at the most fundamental level. Theories are complex and long-winded, but the principles of storytelling are not.

To apply stories to the commercial world, you need to understand how they work at the most fundamental level.

– John Yorke

What is a story?

Let’s take a quick look at a couple of examples.

Jaws — Chief Brody has a problem: the shark. He has to kill shark to save the community.

Bond — James Bond has a problem: Blofeld. He has to kill Blofeld to save the world. (And get the girl.)

So how is this relevant to business?

Well, Bond or Chief Brody is you. The shark/Blofeld is the outside world — the problem you wish to surmount. And the girl or community saved at the end of each story is your reward – from esteem, to pay packet, to promotion.

That’s how stories work — we, through empathy, become the protagonist. We want the same goal that the protagonist wants and we go on the journey with them. How do we bind them (the protagonist) to us (the audience)?

By creating a common enemy.

Alfred Hitchcock once said “The better the villain, the better the picture”. The same is true of all stories. And not just in fiction.

A great practitioner of this approach was an obscure American politician. A former actor turned spokesperson for General Electric.

Let me tell you a story…

In 1964, US democrat Lyndon Johnson was re-elected with the largest majority in history. It was universally agreed that the Republicans were completely unelectable and would not see political office again “for a generation”.

But…

During that campaign, one man made a speech that contained within it the seeds of the Republican party’s recovery and triumph only four years later.

He was introduced modestly on CBS the Tuesday before Election Day, 1964: “Ladies and Gentlemen, we take pride in presenting a thoughtful election address by Ronald Reagan”.

And in half an hour the world shifted on its axis.

[su_youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pbp0hur9RU” responsive=”no” rel=”no” modestbranding=”yes” https=”yes”]

Reagan was a natural charismatic speaker. He was down to earth. He spoke the language of his audience. But most importantly of all, he told a story.

– John Yorke

What was so special about what became known in political circles as “The Speech”?

Reagan was a natural charismatic speaker. He was down to earth. He spoke the language of his audience. But most importantly of all, he told a story.

He didn’t harangue us for not agreeing with him. He told a story as if he were us… and we were him. We were on his side. He created an enemy. And the goal was freedom.

He was Chief Brody, the enemy was the shark, and he was so clever in delineating why his audience should hate that shark, and wish to rise up and defeat that shark, that natural Democrats — people who had never once considered voting Republican — found themselves agreeing with him.

Who was his/the audience’s enemy?

Big Government. A government that was no longer servant, but master of the people. A “patronising liberal elite” who want to tell you how to live your life:

“Welfare scroungers — people like the woman whose husband made $250 a month but who asked for a divorce when she discovered she could make $330 on aid to dependent children. And all while you were trying to get your kids through school and work a bit harder to reward them.”

He was — we were — the little man. And we were invited to stand up to a government he portrayed as (though he never used the term) a Stalinist tyranny.

Right or wrong, it was compelling

Reagan discovered that, “the best measure of a politician’s success was not how successfully he could broker people’s desires, but how well he could tap their fears”. Soon there was a “them” in every speech. And all those folks who were angry at domestic disorder, at immorality, at crime — most of whom would never consider calling themselves conservatives; some of whom had long called themselves liberals — now had a side to join: Reagan’s.

In four years there was a Republican president, and in 12 years Reagan himself — even after the Republican humiliation of Watergate — took the oath of office and ushered in a world — a neoconservative, free-market world — that embodied everything his speech 12 years before had called out for.

The world that, pretty much, we’re living in today.

He did it by telling a story. He gave us a shark (big government), and a Chief Brody (him/us), and if the electorate allowed one to defeat the other we would be rewarded with our freedom.

- The brain science behind good business

- Neurobiology and the importance of character in business stories

- Some case studies

So how does this apply to business?

Politicians are selling an idea. So are you: if you buy this, you will overcome this problem, and get that.

Business narratives work in two obvious ways:

1. Commercials

You see it in commercials the whole time. From Skoda, to Jack Daniels, to Airbnb to Pret a Manger — all their advertising works in the same way. They tell a story.

Bad people made awful food. Pret came along and made good food with care, and people ate it and were rewarded. Bad food was the shark.

2. Brand identity

This is how you tell the story of the brand.

The foundation myth. Just like Spiderman or Superman, the foundation myth (normally a version of “unloved geek has idea that nobody wants, against all odds fights to get it noticed and it takes over the world”) is incredibly seductive.

The Innocent smoothie campaign was a brilliant example — you identify as a geek, go on the journey with them and are rewarded by their love. Airbnb likewise, tells the story of how the little guy — inspired by self-belief — takes over the world.

In both cases — and many others — companies tell their stories to internal and external customers. The customers, suppliers, partners, investors, employees are engaged, identify and come on the journey too. In all cases the structure is the same: you are leading unknowledgeable people to a desired outcome.

For this to work your audience has to empathise — this is the cornerstone, as Reagan knew so brilliantly, of all communication. What did he understand?

The importance of:

- Understanding who you are talking to

- Identifying how and what you can do to make their lives better

- Telling the story in their language

- Communicating how sharing your future can make theirs better

- Making them see the world through your eyes

- Getting them to buy in to that vision.

Once you understand that stories are not just about entertainment, but how the human brain works, you will instinctively understand how to do business differently — in day-to-day operations, including:

- Playing with problems and finding solutions

- Identifying building blocks of change

- Planning roadmaps to take you from A to Z

- Resolving conflict and overcoming tension

- Linking random facts, opinions and experiences into an easily navigable form

- Forming order out of chaos and making difficult facts digestible

- Tapping into universal desires and needs to touch something deep within

- Developing empathy with an audience and connecting with other people.

You can theoretically import any problem into the story machine and resolve it.